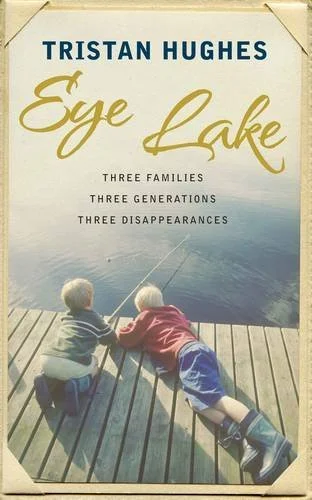

eye lake by tristan hughes

Times Literary Supplement 30 september 2011

There is no explanation offered for why the Eye Lake of Tristan Hughes’s title is so called, other than the rumour that it is because “all the people who’d ever drowned in it looked up from its bed with open eyes”. This air of loss pervades the novel, and our narrator, the simple-minded Eli O’ Callaghan, feels it keenly. Loss is the central fact of his existence: his father, uncle and grandmother are dead; he never knew his mother, and both his grandfather Clarence and his childhood friend George went missing when Eli was a child. The novel opens in 2001 and the town of Crooked River is celebrating its centenary. Eli’s family home, One Callaghan Street, has fallen into disrepair, so he now lives in dorms built as part of The Poplars, a forest business centre that has never taken off. He lives alone, employed as a caretaker for the place, spooked by the sounds he hears from the lake at night. Eli and his family form a contrast to the bullying Bryces. Buddy Bryce owns The Poplars, and he also discovered the iron ore which led to the building of the mine, and, in turn, to the demolition of Eli’s grandfather’s hotel (which had once put Crooked River on the map). Buddy’s son, the almost cartoonishly unpleasant Billy Bryce, was the first baby born in the town in 1972 and Eli was the second: they have been locked in an unequal rivalry ever since. Eye Lake is Hughes’s fourth novel, and, again, place is an important theme. This time he has turned his attention from North Wales, where he grew up, to Canada, where he was born. Hughes is convincing when describing the landscape of Crooked River, less so when it comes to characterization. It is no mean feat, however, to write consistently in the voice of Eli, who is something of an idiot savant, with his inability to read what is happening on the surface and conversely, his flashes of insight. He is conscious that “There’s nowhere more quiet than the places that were loud once”. A new disappearance recalls Evie Wyld’s After the Fire, a Still Small Voice, and Eye Lake has something of the same elegiac quality and flashback structure. It is, however, a quieter book and far from modish so may struggle to win the audience it deserves

This review originally appeared in the Times Literary Supplement