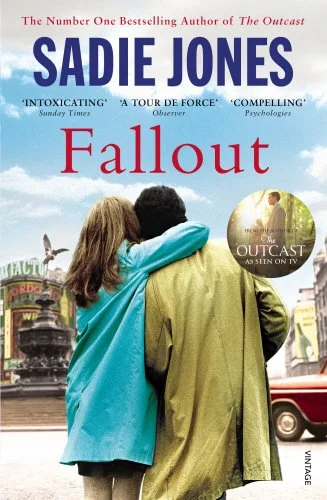

fallout by sadie jones

Times Literary Supplement 16 july 2014

Sadie Jones gives the appearance of being an effortlessly fluent writer. Her sentences tumble forth, occasionally surprising the reader with their odd perfection. Her first novel The Outcast (2008) won the Costa First Novel Award and was also a best seller. Its accessibility obscured for some its psychological insight: it was far more eloquent about self-harm, domestic violence and the insidious workings of shame than dozens of more self-consciously literary novels. At its centre was Lewis, who in Surrey, in the 1950s, must escape the stranglehold of a family into which he does not fit. He finds a counterpart in young Kitty Carmichael whose father beats her until she loses control of herself. Jones's second novel, Small Wars {2009) also examined love and violence in the 1950s. It was only with her third novel The Uninvited Guests (2012) - a haunting pastiche of an Edwardian melodrama - that it became starkly clear what a strange novelist Jones is.

She returns again to the idea of young people who may be able to save each other in her fourth and most accomplished novel, Fallout. Sixth-former Luke has a French mother in an asylum and a Polish father who has become an alcoholic. The young man is "Unentitled. Undesirable. Poor" but also has an instinct that art may redeem him, and one day springs his mother out of the asylum to take her to an exhibition of French painting at the National Gallery. Helene's madness is real and far from sanitized - there are "scorch-marked bruises" on her temples from ECT therapy, but at the exhibition, "They were in the company of greatness and they both knew it and were raised up".

Luke leaves school for the paper mill but he remains relentless in his pursuit of culture. "He obsessed about chord changes, key changes, rhyme schemes and Shakespeare; reading three of four books a week, exhausting the library's parochial shelves. He enjoyed the librarian's girlish thrill at the arrival of the new Agatha Christie or James Bond, and chatted to her about the characters and plot-twists. He read Plato, Proust - to see what the fuss was about". The first time he goes to the theatre - to see Chekov's Three Sisters - ''words that he had felt existed only in the limited contract between his eye and the page were given life".

Jones ably shows her characters' kindness to one another. Luke thinks of his mother as a good mother, in spite of everything-his birth had been "fierce proof to her of her unquench able life". Later, in one of the most moving scenes of the book, when Luke becomes half-demented and is unable to sleep, he asks his friends Leigh and Paul to help him. They lie down on his bed with him as he recites the rosary-the habit, rather than faith, comforting him.

On the night that these three first met, ''They seem the youngest people in the imaginable universe" and Jones is good at conveying the energy and hope of youth. She is also wry about the culture of the 1970s: when they setup the theatre company Graft, a decision is made by one of their associates that the parts of miners in a new play should be played by real miners, not actors.

Jones comments: "The irony of breaking Equity rules to tell a story about the moral stronghold of the NUM did not escape the rest of them". She is also acute about the claustrophobia of theatreland; when a scandal breaks, gossipy luvvies feast on it as though it is a ''full meal".

In contrast to the earnest camaraderie of the autodidact Luke, the steadiness of Paul and Leigh's proto-feminism, is the young actress Nina, who is as blank as she is beautiful. Her mother is a failed actress who has become a bitter cynic. She preys on her daughter's boyfriends before disastrously returning the favour and passing on to Nina one of her own spectacularly unsuitable partners. Leigh and Paul also become a couple and Luke, on realizing this, "smiled as a familiar restlessness overtook; he felt the habitual painful joy of searching and the lack, the lack, the distance from love that was his moulded shape, the fallout that had warped his heart".

He works his way through dozens of women but in Jones's hands his relentless philandering is never entirely heartless or cliched. We understand, like Leigh and Paul, that there is a part of Luke that may be unsound. He nonetheless falls in love with Nina, who has been waiting since childhood to be rescued. On the night he first talks to her, he finds himself ''taking joy in each second as it came" and we desperately want her to be a match for his passion. Jones also offers a startling explanation for Nina's ability to endure the abuse her husband inflicts on her while she is falling in love with Luke: ''The very fact of one thing being done to her so invasively while her heart found safety in another became connected. Pain and freedom, linked by hard sensation, became one". Only once, I felt Jones faltered with a cheap observation before realizing it was written from the perspective of a character who has more cruelty than wit. Sadie Jones is that rare writer who can deliver a satisfying plot without stylistic compromise.

This review first appeared in the Times Literary Supplement