Nicholas Coleridge’s memoir is a rather bracing read: amidst all the gossip and glamour of his life as a magazine supremo, he refers to being molested by a schoolteacher as a young boy, having to identify the body of a colleague who has just died and his father’s Alzheimer’s. This gives the book a rounded sense that it is not a superficial skim through parties and escapades (such as the time he followed the woman who would become his wife, whom he had met once, to India so he could “accidentally” bump into her) that one might expect from the former chairman of Condé Nast. The stories are staggering nonetheless: he gives a funny account of the £100m lawsuit Mohamed Al-Fayed, the then owner of Harrods, brought against Vanity Fair which Coleridge eventually settles with Al-Fayed’s PR man in a steam room (chosen as there was no chance of either of them wearing a wire there).

American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins

American Dirt, the third novel from Jeanine Cummins — who made her name with a memoir about the gang rape and murder of her two cousins — has been described by the crime writer Don Winslow as “a Grapes of Wrath for our time” and selected for Oprah’s Book Club, which almost guarantees a book bestseller status.

Since then, it has been the subject of an intense backlash, partly because Cummins is a white writer from Maryland — her Puerto Rican grandmother notwithstanding — and critics have accused her of cultural appropriation in crassly depicting a Mexican family attempting to cross the border into the United States.

Cummins’s decision to write the novel does not, however, appear thoughtless.

Square Haunting by Francesca Wade

Group biographies are having something of a moment, and Virginia Woolf seems to feature in many of them. In her first book, Francesca Wade has taken the unusual step of not examining Woolf in the context of family, lovers or other members of the Bloomsbury Group, but positioning her alongside other radical women thinkers who lived in Bloomsbury’s Mecklenburgh Square between the wars.

This area of London has been historically praised for its serenity, not least by Isabella in Jane Austen’s Emma, who comments: “Our part of London is very superior to most others! You must not confound us with London in general, my dear sir. The neighbourhood of Brunswick Square is very different from almost all the rest. We are so very airy!”

The best places for fika in London

London may be sick of Scandinavian trends but there is one, fika, which doesn’t involve an entire lifestyle overhaul or the purchase of costly sheepskin rugs. Fika is a communal coffee break taken twice a day in Sweden — usually involving a cup of strong filter coffee and a cinnamon bun. It’s so sacred in Sweden that, famously, even the Volvo car plant breaks for it. The crucial aspects are that it should be communal, savoured, and it should occur away from your desk — so chugging back a Costa latte at the keyboard really doesn’t count. Fika can’t be hurried however, so only those establishments that allow lingering with a friend count. And as the number of Scandinavian-style cafes in London offering slices of princess cake and knotted cardamom buns has expanded enormously in the past years, here is a round up of the best.

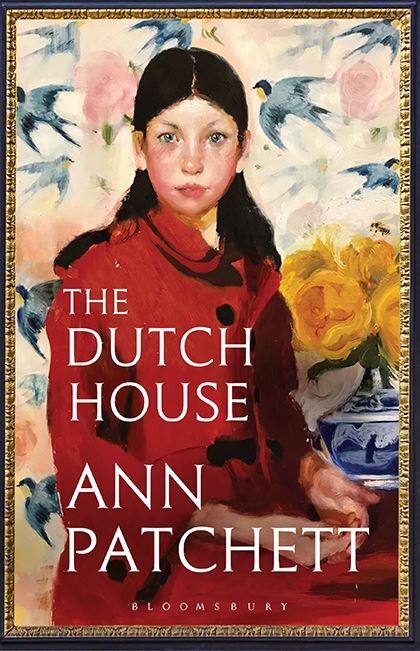

The Dutch House by Ann Patchett

Like the house that gives EM Forster’s Howards End its name, the Dutch House in Ann Patchett’s eighth novel is not always a benign space. It is situated in the suburbs of Philadelphia and was owned by a wealthy Dutch family, the Van Hoebeeks, who abandoned it and left their forbidding portraits, furniture and Delftware behind in 1945. A year later, the house is bought by Cyril Conroy, a realestate developer. But his ascetic wife, stifled by the grandeur of the house, walks out on Cyril and their two children, Maeve and Danny, to instead “help the poor of India.”

Danny narrates the story, which begins in the middle of the 20th century and stretches over 50 years. From the start, he worships his maternal sister Maeve, “her black hair like a blanket down her back.” Maeve is a striking example of Patchett’s ability to make goodness compelling and her set pieces with Andrea, the “silky chinchilla” who marries Cyril and becomes the children’s stepmother, are wonderfully drawn.

Oligarchy by Scarlett Thomas

It sounds in bad taste, but Scarlett Thomas has written a riotously enjoyable novel about a boarding school full of girls with eating disorders. It’s not that Thomas doesn’t take eating disorders seriously; she takes them so seriously that one of the girls dies. But there are few more vivaciously original novelists around today, and surely none of them is having as much fun while making serious points. Elsewhere, Thomas has written compellingly about her own orthorexia (or obsessive desire to control her diet); but this doesn’t mean that she is above lampooning the hysterical pronouncements of the diet-obsessed — not least that fruit, unless you pick it in the wild yourself, contains so much sugar that you may as well eat Haribo, which is nicer, after all.