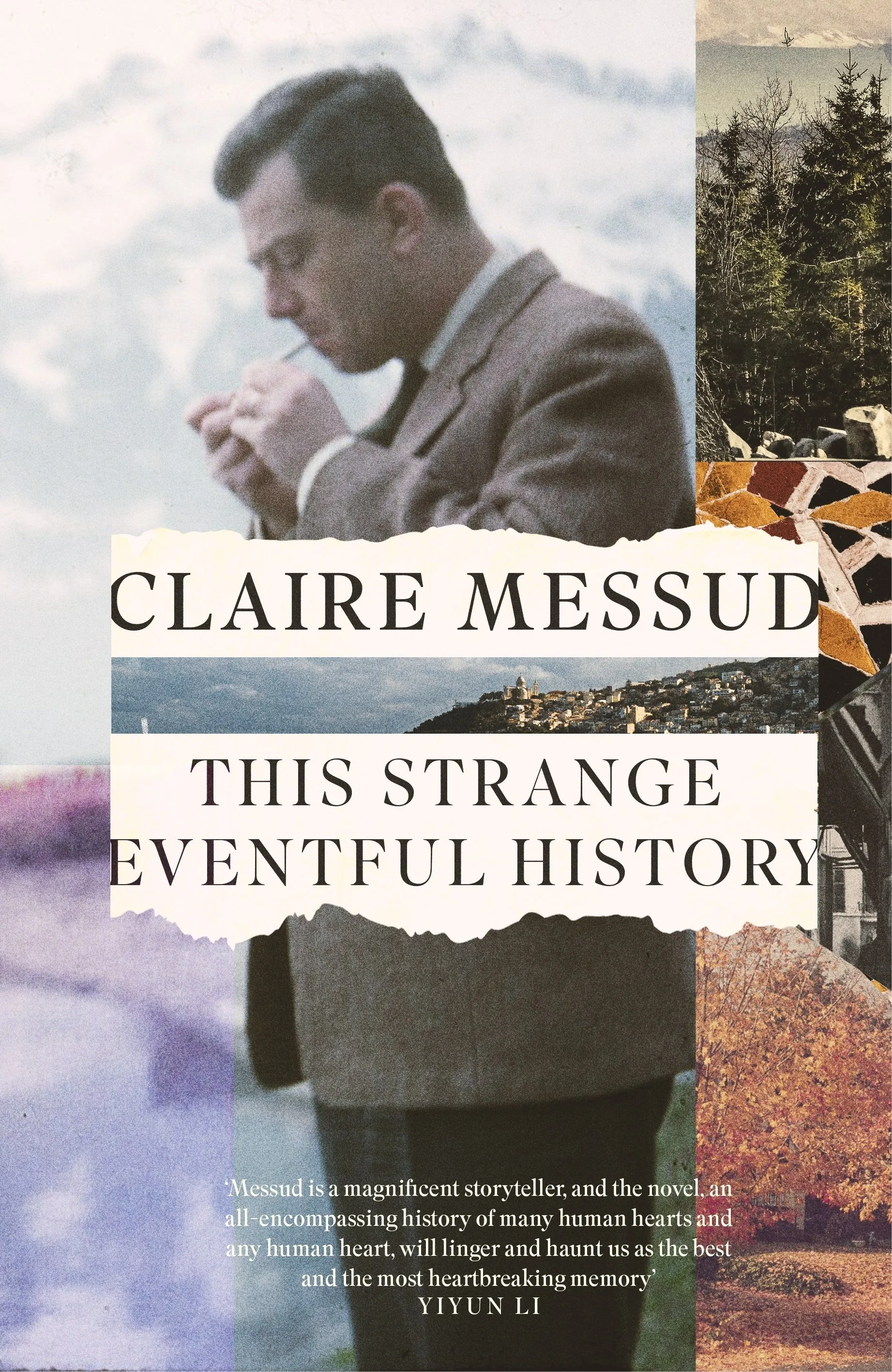

this strange eventful History by claire Messud

the daily telegraph 10 may 2024

Claire Messud’s fourth novel, The Woman Upstairs (2013), was notable for having a genuine twist – a reminder of how rare that is in literary fiction. Messud has nonetheless produced such a rarity again in This Strange Eventful History.

For her seventh novel, the saga of the Cassar clan, Messud has turned to her own family history. The novel reaches from Algeria, where her paternal grandparents were raised, to Connecticut, where Messud herself was born, and from 1927 to 2010. The Cassar family go to war, move continents, develop dementia and alcoholism, and marry or fail to: this is not a milieu in which remaining single is viewed as a dignified choice.

This Strange Eventful History is told in the third person: Gaston is the Cassar patriarch, and while he and his wife Lucienne consider their marriage to be “the masterpiece” of their lives, it contains a troubling secret. Their children, François and Denise, are unaware of this secret – as is the reader, until the end of the book – and bewildered that they’ve been unable to achieve the same happiness in their own lives.

The elder sibling, François, grows up to work for an aluminium company in Canada, where he lives with his disappointed wife Barbara. He’s ground down by a sour marriage and a dull job that never pays enough; he feels he has lost “interior space”.

By contrast, Denise remains unmarried and is much-pitied, attending to their father in his old age. It’s testament to the novel’s subtlety that it makes Denise sympathetic and not clichéd, even as her sister-in-law despises her “relentless bonhomie” and “prominent yellow teeth”. Messud writes Denise from the inside out, showing us that hatred, but also some of Denise’s quiet domestic contentment.

This Strange Eventful History may be Messud’s finest book. Though it’s rarely joyous, it’s consistently absorbing. Fellow novelist Yiyun Li blurbs it as “the War and Peace of the 20th and 21st century”; yet the writer of whom Messud reminded me most was Balzac, in her ability to create a rich family saga without neglecting vivid descriptions of everyday objects, such as a melon with “beautiful orange flesh so juicy and redolent it was almost high”.

This review originally appeared in The Daily Telegraph