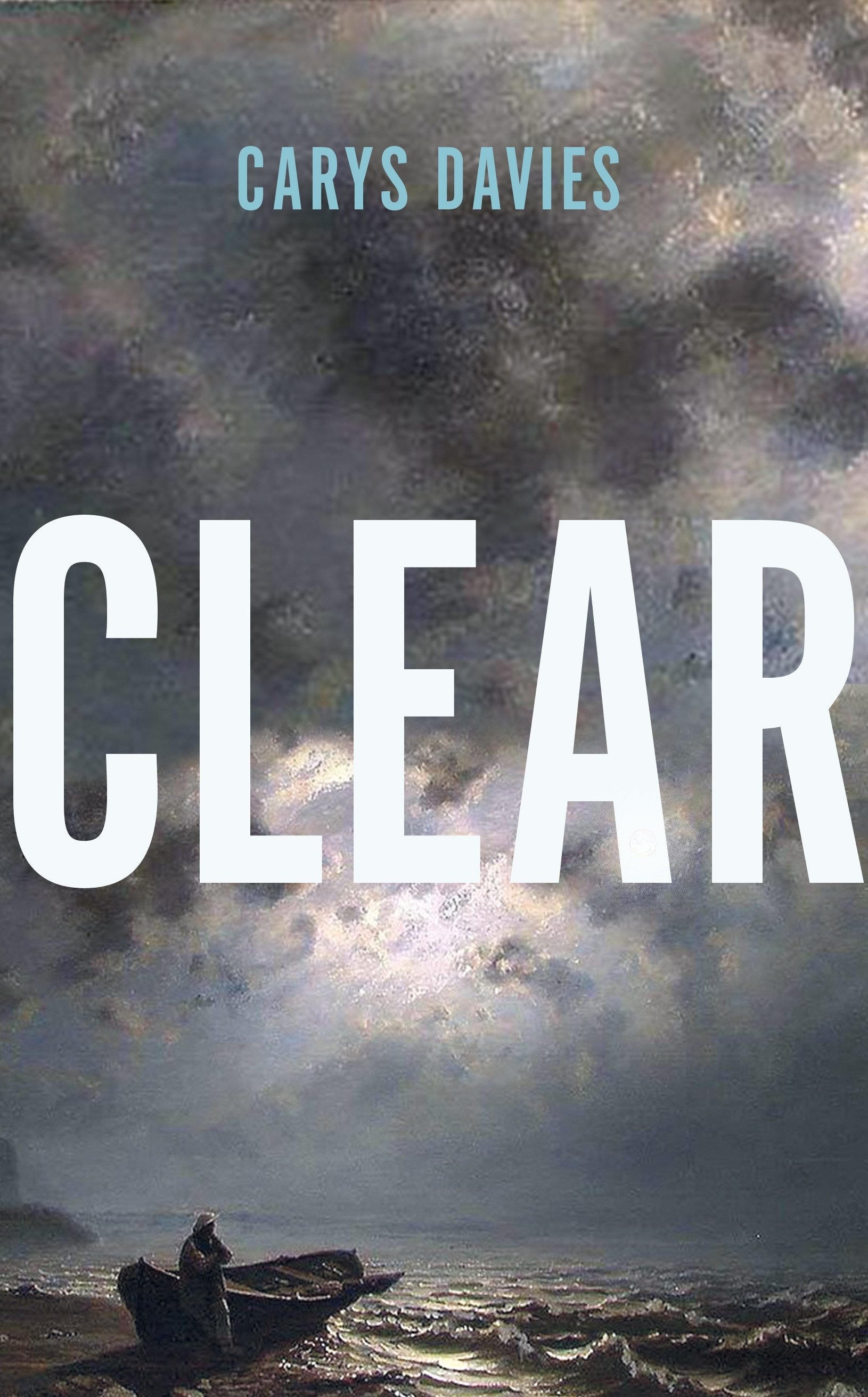

Carys Davies grew up in Newport, south Wales but her novels have been set in 19th- century Pennsylvania (West, 2018), contemporary Ooty in India (The Mission House, 2020) and now a small island off the north coast of Scotland in 1843. Her short stories have been set variously in the Australian outback and Siberia. She has said that when creating a fictional world, ‘I seem to require a certain kind of distance from my own life’.

On an island ‘between Shetland and Norway’, a man called Ivar lives in isolation, talking only to Pegi the horse, whom he calls ‘old cabbage and a silly, odd-looking person’. One day he finds a man naked and unconscious on the beach below the cliffs. Even after the man regains consciousness, he and Ivar do not share a common language, so communication between them is halting. The newcomer is John Ferguson, a church minister who has been sent to evict Ivar so that the land can be used solely by grazing sheep.